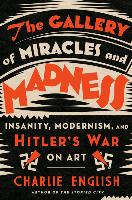

The untold story of Hitler's war on "degenerate" artists and the mentally ill that served as a model for the "Final Solution."

"A penetrating chronicle . . . deftly links art history, psychiatry, and Hitler's ideology to devastating effect."-The Wall Street Journal

As a veteran of the First World War, and an expert in art history and medicine, Hans Prinzhorn was uniquely placed to explore the connection between art and madness. The work he collected-ranging from expressive paintings to life-size rag dolls and fragile sculptures made from chewed bread-contained a raw, emotional power, and the book he published about the material inspired a new generation of modern artists, Max Ernst, André Breton, and Salvador Dalí among them. By the mid-1930s, however, Prinzhorn's collection had begun to attract the attention of a far more sinister group.

Modernism was in full swing when Adolf Hitler arrived in Vienna in 1907, hoping to forge a career as a painter. Rejected from art school, this troubled young man became convinced that modern art was degrading the Aryan soul, and once he had risen to power he ordered that modern works be seized and publicly shamed in "degenerate art" exhibitions, which became wildly popular. But this culture war was a mere curtain-raiser for Hitler's next campaign, against allegedly "degenerate" humans, and Prinzhorn's artist-patients were caught up in both. By 1941, the Nazis had murdered 70,000 psychiatric patients in killing centers that would serve as prototypes for the death camps of the Final Solution. Dozens of Prinzhorn artists were among the victims.

The Gallery of Miracles and Madness is a spellbinding, emotionally resonant tale of this complex and troubling history that uncovers Hitler's wars on modern art and the mentally ill and how they paved the way for the Holocaust. Charlie English tells an eerie story of genius, madness, and dehumanization that offers readers a fresh perspective on the brutal ideology of the Nazi regime.