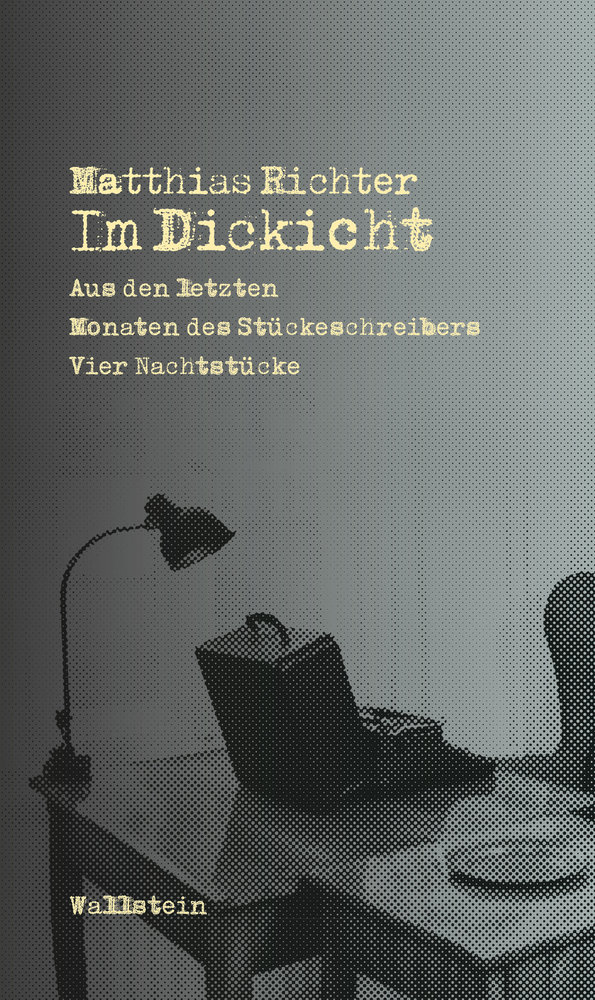

Brecht und wir? Brecht heute? Kritische Nachfragen in literarischen Phantasien»Ändere die Welt: sie braucht es!« Schlagender hat kein deutschsprachiger Autor den revolutionären Appell formuliert als Bertolt Brecht. Die Welt umzukrempeln und die kommunistische Utopie zu verwirklichen - daran hielt er bis zu seinem Tod eisern fest. In sein Inneres aber konnte niemand blicken, vielleicht noch nicht einmal er selbst. Christa Wolf war irritiert über »diese konstante Weigerung, über sich zu reflektieren«. Und Max Frisch stellt in seinen Erinnerungen an Brecht fest: »Wir kannten ihn nicht«.Das ist der Ausgangspunkt für die literarischen Phantasien dieser vier Nachtstücke aus den letzten Monaten des Stückeschreibers Frühjahr und Sommer 1956: als ihm in der Berliner Charité klar wird, dass sein Herz nicht mehr lange mitmachen wird und seine politische Weltsicht vielleicht genauso wackelig ist; als der Besuch seines Verlegers dazu führt, dass er in maßlosem Hass auf Thomas Mann versinkt; als die junge, hübsche, kluge Praktikantin seine meisterhaften Gedichte widerborstig vom Kopf auf die Füße stellt; als schließlich ein Interview für das Time Magazine im Desaster endet.In der Figur des Stückeschreibers steckt einiges, das von Bertolt Brecht geborgt ist. Trotzdem ist der Stückeschreiber eine Phantasiegestalt. »Im Dickicht« ist eine Fiktion. Sie dreht sich um eine Frage: Warum eigentlich konnte Brecht seinem Dämon nicht mit der gleichen Energie widerstehen, mit der er Gegner bekämpfte? Warum versteckte er sich und schwieg hartnäckig, um sich mehr und mehr in die Rolle des linkisch-listigen Freundlichen, gleichwohl immer Überlegenen zurückzuziehen?