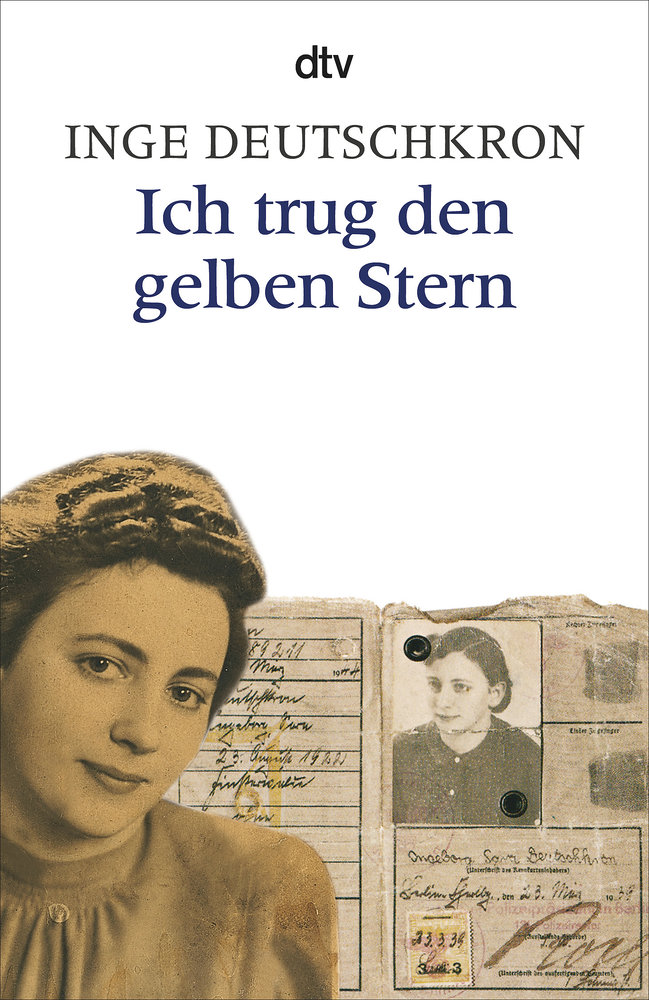

Ein Dokument über Entrechtung, Verfolgung, Deportation und Tod, über Illegalität und Identitätsverlust und zugleich stiller menschlicher Hilfsbereitschaft.

Viele Angehörige der älteren Generation erinnern sich noch daran, wie die Nazis ihre Kindheit mißbrauchten, ohna daß sie dies damals erfassen konnten. Wie aber erlitten die Söhne und Töchter jüdischer Eltern diese Zeit? Inge Deutschkron, in Berlin aufgewachsen, mußte erfahren, was es heißt, ein jüdisches Kind zu sein. Zunächst bedeutete dies nur, nicht mit Gleichaltrigen spielen zu können, vom Schwimmen- und Sportunterricht ausgeschlossen zu sein, mehrmals die Schule zu wechseln und in andere Stadtviertel umzuziehen zu müssen. Allmächlich kommt die Angst vor Verhaftungen zuinzu, und bald wird der Familie klar, daß es sich um eine planmäßige Diskriminierung handelt, an deren Ende die totale Menschenverachtung und Mord stehen.

Der Ausbruch des Krieges verhindert die Emigration. Ab 1941 mußten die Juden den gelben Stern tragen, die ersten Deportationen unter den 66 000 Berlinern Juden setzten ein. Die verzweifelte Angst vor dem offenbar unausweichlichen Schicksal wurde übermächtig. Für Inge Deutschkron und ihre Mutter begann nun ein Leben in Illegalität, unter fremder Identität, lebensbedrohend für sie selbst wie für ihre Freunde, die ihnen in menschlicher Solidarität Beistand gewährten.

Nach Jahren der quälenden Angst vor der Entdeckung haben sie schließlich den bürokratisierten Sadismus des nationalsozialistischen Systems überlebt: zwei unter 1423 Juden in Berlin, die dem tödlichen Automatismus entronnen sind.